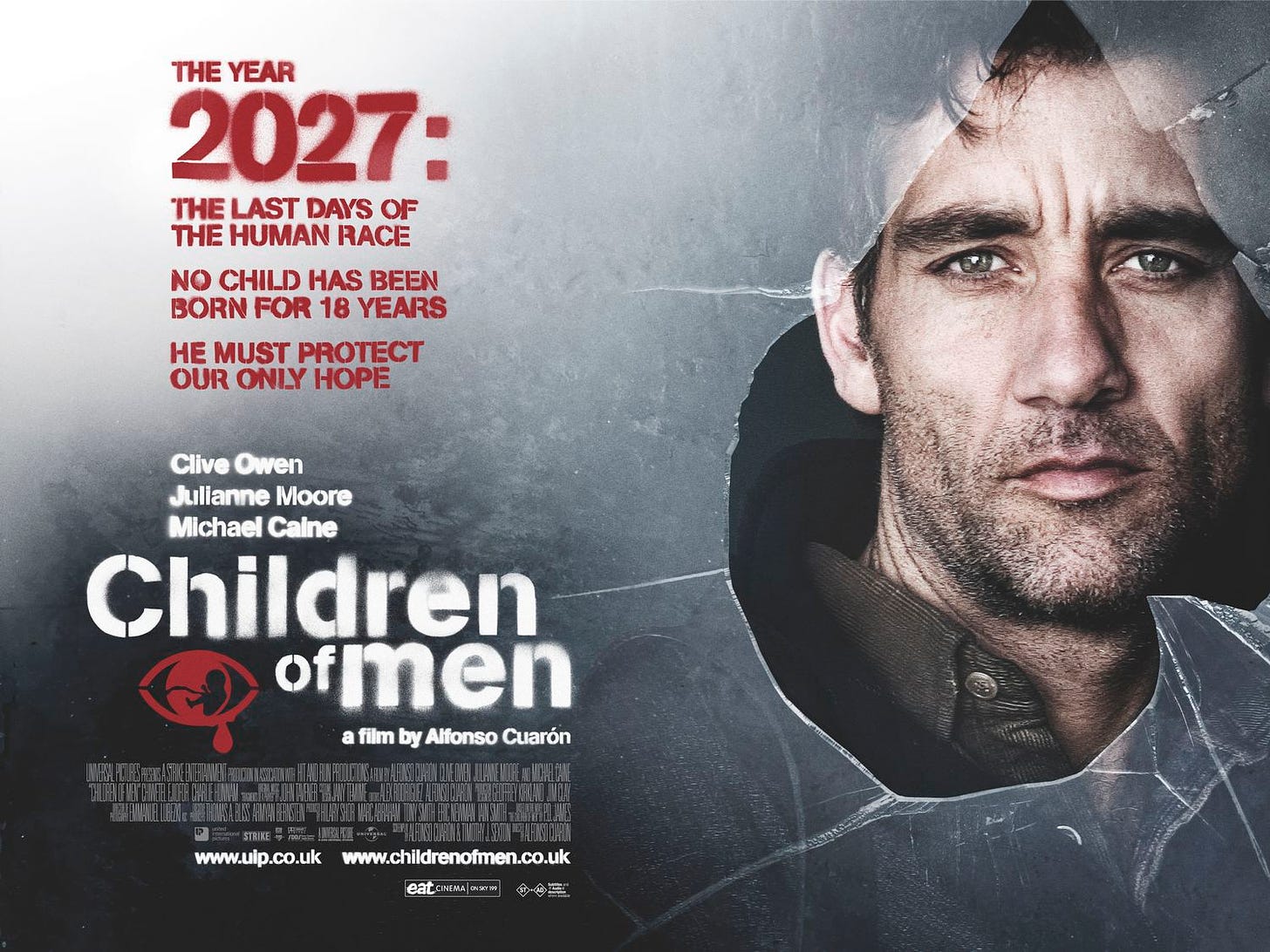

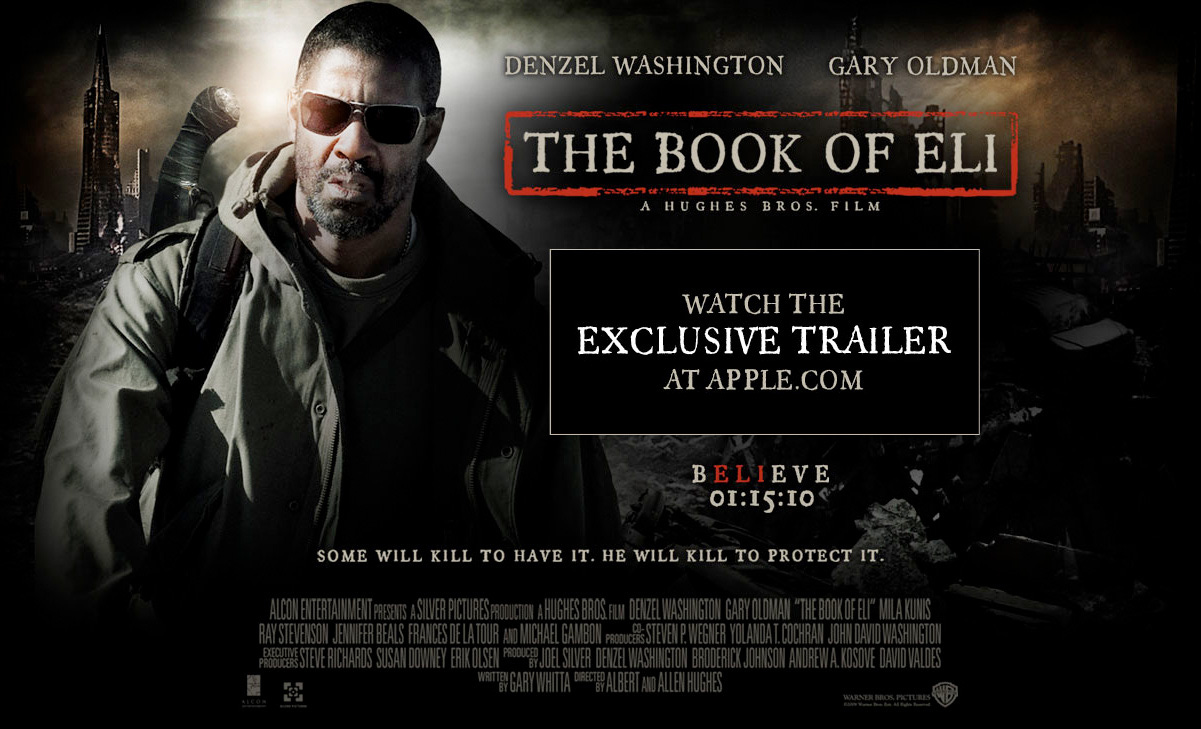

Stream On: Good shepherds of ‘Children of Men’ and ‘The Book of Eli’

Two dystopian post-apocalyptic thrillers in which the hope for humankind’s rebirth is at risk.

Two dystopian post-apocalyptic thrillers in which the hope for humankind’s rebirth is at risk. In the first, it’s a baby, born 18 years after worldwide infertility threatens humanity; in the second, it’s an ancient book protected by a pilgrim for 30 years since “the final war.”

/Amazon /Prime Video /Streaming /Trailer /2006 /R

The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them. (Isaiah 11:6, King James Bible)

“It’s very odd, what happens in the world without children’s voices.”

Children of Men opens in London with a headline news roundup for November 16, 2027: “Day 1,000 of the siege of Seattle.” “The Muslim community demands an end to the army’s occupation of mosques.” “The Homeland Security bill is ratified.” “After eight years, British borders will remain closed. The deportation of illegal immigrants will continue.”

“Good morning. Our lead story: The world was stunned today by the death of Diego Ricardo, the youngest person on the planet. “Baby” Diego was stabbed outside a bar in Buenos Aires after refusing to sign an autograph. The fan was later beaten to death by an angry crowd.”

In a coffee shop, Theo Faron (Clive Owen) picks up a coffee to go and heads out to the street, as the report continues. “Diego Ricardo, the youngest person on the planet, was 18 years, four months, 20 days, 16 hours and eight minutes old.”

Faron stops at a nearby bench to pour some whiskey into his coffee, and the camera, which has been tracking him, swivels around as the shop from which he came is destroyed in an explosion. “CHILDREN OF MEN” appears on the screen.

Faron, a former activist turned cynical bureaucrat, is snatched up in the street by the Fishes, a militant immigrant-rights group led by his estranged wife, Julian Taylor (Julianne Moore). Julian offers him money to acquire transit papers for a young refugee woman (and illegal immigrant) named Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey). Luke, a Fishes member, drives Faron, Kee, Julian, and a woman named Miriam towards Canterbury when an armed gang ambushes them and kills Julian. Two police officers later stop their car; Luke kills them and the group hides Julian's body before heading to a Fishes safe-house. (This four-minute set piece by cinematographer Emanuel Lubezki defies description; it was apparently shot in one take, in real time, by one camera moving inside and out of the ambushed car, and involves the choreography of: a repeated stunt with a ping-pong ball; another, burning, car rolling into their way; a crowd attacking from the woods; two people on a motorcycle shooting into the host car; the crash of the motorbike; a police car chasing them; and more. Here is that isolated tracking shot.)

At the safe-house Kee reveals to Faron that she is pregnant—the only known pregnant woman in the world. Julian had intended to bring her to the Human Project, a secretive scientific group dedicated to curing humanity's infertility. Luke persuades Kee to stay, and he is voted the new leader of the Fishes. That night, Faron learns that Julian's death was orchestrated by the Fishes so that Luke could become their leader, and overhears that they intend to kill him, Faron, and use the baby as a political tool to support their coming revolution. Faron awakens Kee and Miriam, who is her midwife, and they escape to the secluded hideaway of Faron's friend Jasper Palmer (Michael Caine, Hanna and Her Sisters). They make plans to board the Human Project ship, the Tomorrow, which will arrive offshore at Bexhill-on-Sea disguised as a fishing vessel, when they are caught up in the Fishes’ revolt.

The critics’ consensus at Rotten Tomatoes reads, “Children of Men works on every level: as a violent chase thriller, a fantastical cautionary tale, and a sophisticated human drama about societies struggling to live.”

THE BOOK OF ELI (Official site)

/Amazon /Prime Video /Streaming /Trailer /2010 /R

And the word of the Lord was precious in those days; there was no open vision. And it came to pass at that time, when Eli was laid down in his place, and his eyes began to wax dim, that he could not see. (1 Samuel 3:1b-2, King James Bible)

The Book of Eli opens on a camouflaged hunter collecting protein with a bow and arrow in what looks like a nuclear winter. The forest floor shows a human cadaver next to a broken revolver. The hunter stuffs his prey into a sack and walks off down a road past some wrecked autos in a grey landscape. Soon he finds a shack; inside, a suicide hangs from the ceiling. He takes the shoes from the corpse, builds a cooking fire and shares some of his catch with a mouse that appears. “You hungry? You know you got to come get it. Don’t play hard to get. You’ll like it: it’s cat! There you go,” as the mouse accepts the meat and retreats back into the wall.

The hunter, a pilgrim, puts in earbuds and from an ancient Walkman he selects Al Green’s “How Do You Mend a Broken Heart?” as he sharpens his knives, washes up and beds down after reading from a book, moving his lips, as if in prayer.

“I can think of younger days when living for my life was everything a man could want to do. I could never see tomorrow—I was never told about the sorrow.”

Next day, on the road again, and a ragged woman asks for his help with her shopping cart, which apparently contains all of her possessions. He says, loudly, “You know, the only good thing about no soap? You can smell hijackers a mile off!” Sure enough a gang reveals itself and surrounds him. The leader demands he dump his pack out on the ground.

“Can’t do that.”

The leader smacks the pilgrim’s arm. “Are ya listenin’ to me?”

“I am now. You listenin’ to me? Put that hand on me again, you won’t get it back.”

“Do you believe this guy?” The leader grabs for the pilgrim’s pack, and after a flash and the ring of steel, he pulls back a stump. “What’d you do that for? He just cut my hand off!” Slumping to the ground he hollers to his group, “What are you standing around for? Kiss him!”

The hijackers exchange looks. “What’d he say?” The pilgrim, Eli (Denzel Washington, Malcolm X, Unstoppable, Fallen), says. “He’s in shock. I think he means ‘kill him.’”

The Book of Eli writer Gary Whitta said, in an interview, “For me, the original idea for the film before the faith-based elements and the ideas of literacy, I just wanted to make a samurai movie. I just wanted to make a bad-ass take on that mythic wandering hero since that’s a classic character,” and true to form, Eli, attacked by the gang with swords, knives, even a chainsaw, kills them all in a few moments of beautifully choreographed martial arts.

Eli’s book, that he read from the previous evening, is the last remaining copy of the King James Bible—all the other copies were intentionally destroyed following the past nuclear war. He was led to the book by a voice in his head, directing him to travel westward to a place where it would be safe, and assuring that he would be protected and guided on his journey. That’s before he comes to a settlement led by Carnegie (Gary Oldman, The Fifth Element), a literate pirate also looking for a copy of the Bible, which he remembered from his youth, and which he thinks can be used to wield power, and which he will do anything—anything—to obtain.

The Book of Eli had a harder time with the critics, but I, and friends to whom I’ve shown it, like it a lot. One of the positive reviewers at Rotten Tomatoes wrote, “Directors Albert and Allen Hughes lean into the allegorical elements, making it a badlands spaghetti western by way of a holy mission and a science fiction frontier thriller that embraces the possibility of miracles.”

Pete Hummers is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to earn fees by linking Amazon.com and affiliate sites. This adds nothing to Amazon's prices. This column originally appeared on The Outer Banks Voice.