Stream On: Don’t mess with Stanley Kubrick!

What happens when one attempts a sequel to a Stanley Kubrick movie.

Legendary 20-century director Stanley Kubrick famously put his own stamp on works he adapted—Stephen King hated Kubrick’s treatment of his The Shining, but earlier, Arthur C. Clarke threw in with Kubrick when he co-wrote the screenplay of 2001: A Space Odyssey with the finicky director, from Clarke’s own pulpy 1948 space tale, “The Sentinel of Eternity,” and the result was typical Kubrick—that is, a masterpiece.

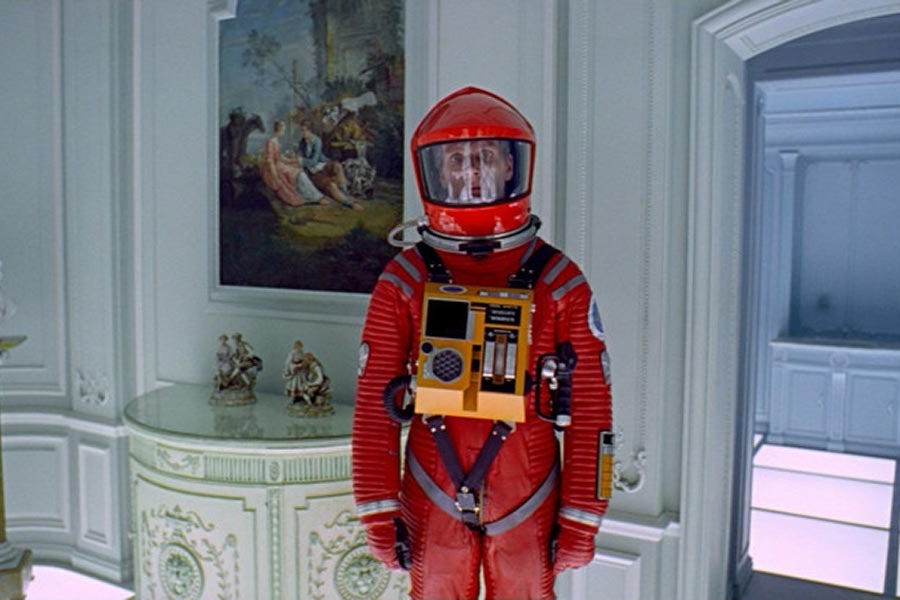

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

/Amazon /Prime Video /Streaming /Trailer /1968 /G

“This conversation can serve no purpose anymore.” (HAL-9000, an artificial intelligence)

It’s almost like Arthur C. Clarke’s 1948 Avon Fantasy Reader story came across one of the black monoliths of 2001 and became reborn, from an admittedly fine yarn about alien intervention in human history to a profound meditation on humanity itself.

A brilliant exercise in cinematic storytelling, that is, outlining a narrative that’s larger than mere prose or theater, 2001: A Space Odyssey tells its tale through cinematic vignettes and music. The screenplay is only 65 pages long, very short for a 160-minute movie, and most of it is stage direction—there are 88 minutes without any dialogue, and what dialogue there is, is deliberately mundane.

It tells the tale of the discovery of four monoliths, the first discovered at “the dawn of man.” A tribe of vegetarian proto-humans find it on the African plain; it’s standing on end, about nine feet high by four feet wide by one thick, a perfectly smooth, rectangular cuboid that emits an audible signal, and the hominids are drawn to it, and run their paws over it.

Anthropologists say that the first humans—homo habilis—made and used tools, and I think it’s reasonable to assume the first tools were weapons. A candle of tapirs (that’s the collective noun) had been co-existing with the hominids, competing for roots, but since the monolith, they are prey. Similarly, a nearby tribe of Australopithecus that had previously engaged in breast-beating displays with the hominids discover that their foes now have weapons (tapir bones) and an Australopithecus is killed during their next encounter.

When a homo habilis, feeling pretty good about himself, flings a bone into the air, a jump cut takes us into space, three million years later, as an Ares IB moon shuttle arrives on earth’s moon to investigate a monolith that has just been discovered there, apparently buried millions of years previous by beings unknown. The soundtrack changes from ambient sounds to the beautiful and timeless classical music of Johann and Richard Strauss, and György Ligeti’s mysterious-sounding “Atmosphères.”

When the second monolith is unearthed (or un-mooned, as it were), it sends a signal to the planet Jupiter, and so a team is sent there. Only one astronaut, Dr. Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea), survives a battle with the ship’s onboard artificial intelligence “HAL-9000,” and when he finally reaches the third monolith, between Jupiter and its moon Io, Bowman (and the viewer) find a fourth monolith—and what might be the ultimate mystery. Curtain.

2010: THE YEAR WE MAKE CONTACT

/Amazon /Prime Video /Streaming /Trailer /1984 /PG

“My God! It’s full of stars!” (David Bowman)

Accompanied by stills from 2001, 2010 presents its backstory like a computer runout, ending with “COMMANDER DAVID BOWMAN ENCOUNTERED OBJECT BETWEEN JUPITER AND IO. THE OBJECT IDENTICAL TO MONOLITH FOUND ON THE MOON … EXCEPT IN SIZE.

“MONOLITH NEAR JUPITER IS TWO KILOMETERS LONG. COMMANDER BOWMAN LEFT DISCOVERY TO INVESTIGATE. LAST TRANSMISSION FROM COMMANDER BOWMAN:

“MY GOD, IT’S FULL OF STARS.”

Dr. Heywood Floyd, from the second act of 2001 (but now played by Roy Scheider) is approached by a Soviet scientist in 2010. (The film was made in 1984, when the Soviet Union was still in existence.)

Nine years before, he had dissembled before a group of Russian scientists on his way to USA lunar outpost Clavius to investigate the four-million-year-old monolith that had been dug up on the moon. The United States National Council of Astronautics had wanted to keep its existence secret while they investigated it; of course, and as of 2010 there had still been no answers, only Commander Bowman’s disappearance. Now the Soviets have found Bowman’s abandoned ship Discovery and request Floyd’s help.

While the previous paragraph contained almost all of the exposition of the previous film, 2010 proceeds like a regular narrative, with plenty of dialogue from all comers. The transition is a little difficult for me: 2001 was decidedly impressionistic in tone, and each viewer took away something different. (Arthur C. Clarke’s 1948 short story “The Sentinel of Eternity”—read it here—which was the starting point for the earlier movie, was written in the first person of one of the monolith’s discoverers, in florid prose almost approaching James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 Last of the Mohicans. 2001 screenwriters Clarke and Kubrick were able to transform that pulp science fiction into high art.)

In 1982 Clarke wrote a sequel to the 1968 novel that he wrote concurrently with the film 2001. 2010: Odyssey Two was adapted as 2010: The Year We Make Contact. When Clarke published Odyssey Two, he telephoned Kubrick, and jokingly said, “Your job is to stop anybody [from] making it [into a movie] so I won’t be bothered.” Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer worked out a contract to make a film adaptation, but Kubrick had no interest in directing it. Been there, done that. However, Peter Hyams was interested and contacted both Clarke and Kubrick for their blessings, and according to Hyams, “Kubrick more or less said, ‘Sure. Go do it. I don’t care.’ And another time he said, ‘Don’t be afraid. Just go do your own movie.’”

Hyams did, and the differences between the two movies are stark, but 2010 has its own charms. When we accept that it’s a conventionally told science fiction story, we see the good characters (and actors including Helen Mirren, John Lithgow and Bob Balaban), good direction (and I think some of the same sets), and suspenseful moments, but a payoff not substantially different than 1951’s The Day the Earth Stood Still.

Still, it’s worth a watch, but not immediately after 2001. Maybe wait nine years?

Pete Hummers is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to earn fees by linking Amazon.com and affiliate sites. This adds nothing to Amazon’s prices. This column originally appeared on The Outer Banks Voice.