Stream On: Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles take on Little Red Riding Hood

Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and The Stranger (1946)

“A clear horizon—I think that’s as happy as I’ll ever want to be.” (Alfred Hitchcock)

A clear horizon holds no threats, and if you think that threats are obvious, consider a wolf disguised as your grandma, a serial killer running from the law with his unsuspecting sister’s middle-class family in the idyllic suburbs, or a charming Nazi running from the U.N. War Crimes Commission in small-town Connecticut.

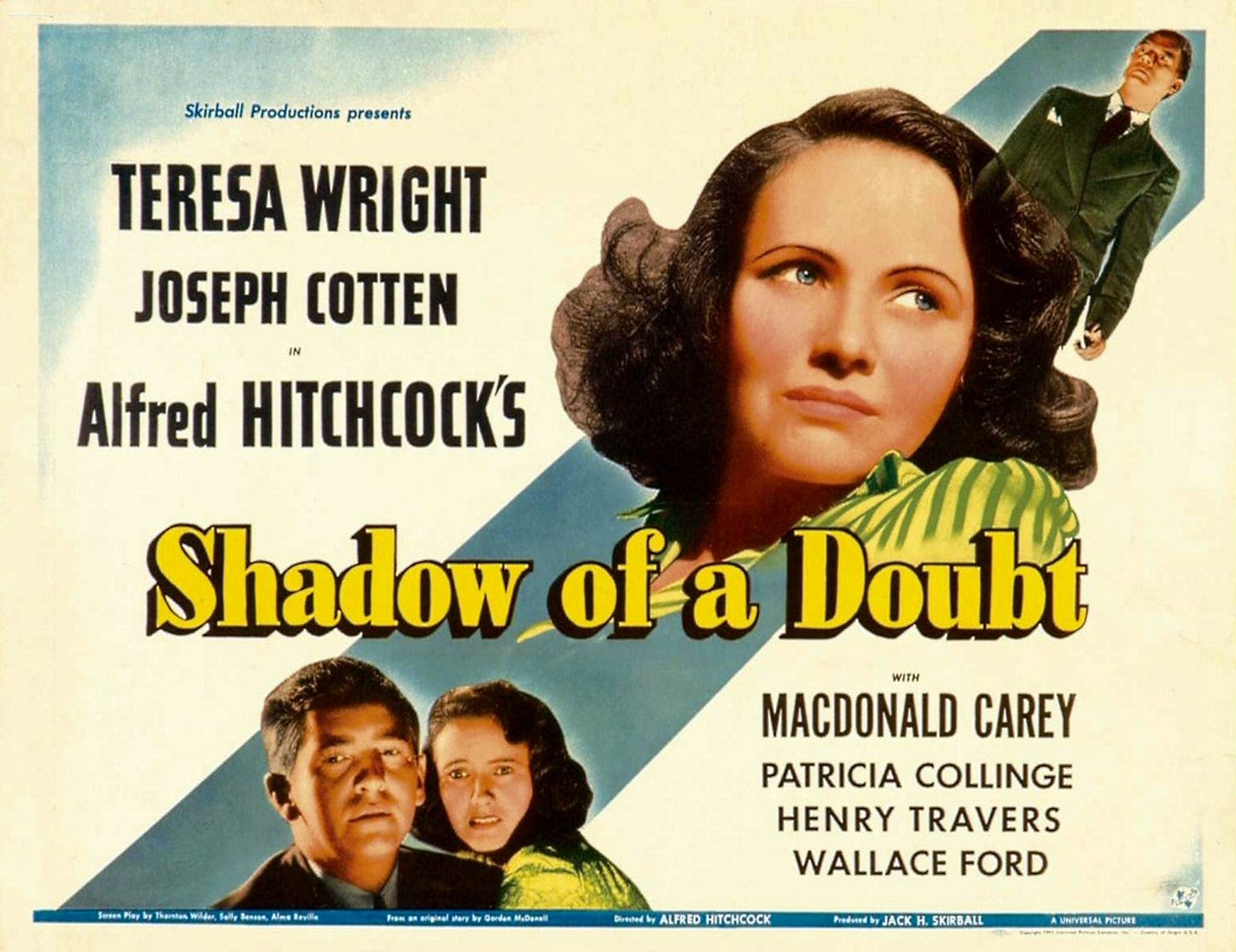

SHADOW OF A DOUBT

/Amazon.com /Prime Video /Streaming /Trailer /1943 /PG

Alfred Hitchcock told Dick Cavett in 1972 that Shadow of a Doubt was his personal favorite of his own films. It is quintessential Hitchcock, a tale of the monster under the bed that will no longer stay hidden. Teresa Wright plays Charlie, a bored suburban teenager who struggles against the ennui of her anodyne life. She is cheered by the sudden visit of her uncle Charles (Joseph Cotten) from the east.

The film’s noirish prologue economically fills in the background: We see Charles, in an apparent afterglow, lying on his bed in a cheap Philadelphia boarding house, but with a pile of money on the nightstand. His landlady tells him that two gentlemen were inquiring after him, and soon we see him getting off a train in a charming sun-drenched California town. (Thornton Wilder, author of the small-town anthem Our Town, wrote the screenplay with Sally Benson, who later wrote Viva Las Vegas, and Alma Reville, Hitchcock’s wife.)

Santa Rosa is picture-perfect, with porch-lined streets and a traffic cop downtown who knows everyone’s name. Charles’ sister’s family is worthy of a Norman Rockwell calendar and includes a young son; a bookish, bespectacled daughter; teenaged Charlie; and a husband who works in the local bank. In a droll nod to Hitchcock’s world, Charles’ brother-in-law and his neighbor (Hume Cronyn) love to discuss the perfect murder, both being avid mystery fiction readers.

It gradually becomes apparent to the audience, and young Charlie, that Uncle Charles is one of two suspects being sought in connection with a series of widow murders back east, in part from a pair of detectives who show up in town in a callback to the prologue. Charles’ remarks at dinner give Charlie the first hint that something … is not right:

“The cities are full of women, middle-aged widows, husbands, dead, husbands who’ve spent their lives making fortunes, working and working. And then they die and leave their money to their wives, their silly wives. And what do the wives do, these useless women? You see them in the hotels, the best hotels, every day by the thousands, drinking the money, eating the money, losing the money at bridge, playing all day and all night, smelling of money, proud of their jewelry but of nothing else, horrible, faded, fat, greedy women … Are they human or are they fat, wheezing animals, hmm? And what happens to animals when they get too fat and too old?”

THE STRANGER

/Amazon.com /Prime Video /Streaming /Trailer /1946 /NR

Orson Welles was an admirer of Shadow of a Doubt (and a friend of Joseph Cotten); he was given a chance to direct The Stranger when original choice John Huston entered the military, with the stipulations that he complete it on time and under budget. He agreed to defer to the studio in any creative dispute, and the result was his only box-office success.

“Mr. Wilson (Edward G. Robinson) is an agent of the United Nations War Crimes Commission who is hunting for Nazi fugitive Franz Kindler (Welles), a war criminal who has erased all evidence which might identify him. He has left no clue to his identity except ‘a hobby that almost amounts to a mania—clocks.’

“Wilson releases Kindler’s former associate Meinike, hoping the man will lead him to Kindler. Wilson follows Meinike to a small town in Connecticut, but loses him before he meets with Kindler. Kindler has assumed a new identity as ‘Charles Rankin,’ and has become a teacher at a local prep school. He is about to marry Mary Longstreet (Loretta Young), daughter of a Supreme Court Justice, and is involved in repairing the town’s 400-year-old Habrecht-style clock mechanism that crowns the belfry of a church in the town square” (Wikipedia).

It’s a misdirectional speech from Rankin at a dinner party, reminiscent of Uncle Charles’ speech in Shadow of a Doubt, that gives him away to Wilson: “The German sees himself as the innocent victim of world envy and hatred, conspired against, set upon by inferior peoples, inferior nations. He cannot admit to error, much less to wrongdoing, not the German…. Mankind is waiting for the Messiah, but for the German, the Messiah is not the Prince of Peace. No, he’s … another Barbarossa … another Hitler.”

Mr. Wilson: “Not Marx?”

Rankin: “But Marx wasn’t a German—he was a Jew!”

Mr. Wilson is convinced and calls his office to report that Rankin “is above suspicion,” but in the middle of the night he recalls Rankin’s last remark, and rescinds his opinion: “Who but a Nazi would say that Marx wasn’t a German because he was Jewish?”

It was only when I watched these two films in two days that I realized they were the same story—but with completely different details. They make a great double feature.

Pete Hummers is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to earn fees by linking Amazon.com and affiliate sites. This adds nothing to Amazon’s prices.