Stream On: A pocketful of Gould

Roger Ebert wrote in 1969 that “Elliott Gould emerges, not so much a star, more of a ‘personality.’ He’s very funny.”

When I recently watched Ray Donovan, I was delighted to see a wonderful Elliott Gould among the cast as Ray’s quirky employer. From a part in Norman Lear’s clumsy 1968 farce The Night They Raided Minsky’s, Elliott’s star rose precipitously to where he became one of the faces of the nascent Hollywood counterculture (and has been hard at work ever since). After co-starring in Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (which remained relevant all the way to 1973, when a sitcom was attempted, lasting two months) in 1969, Roger Ebert wrote that “Gould emerges, not so much a star, more of a ‘personality,’ like Severn Darden or Estelle Parsons. He’s very funny.”

His eye had a certain twinkle that easily saw him through Robert Altman’s 1970 satirical milestone M*A*S*H, which was set in Korea, but was about America’s involvement in Viet Nam, after which he appeared on the cover of Time Magazine as a “star for an uptight age.”

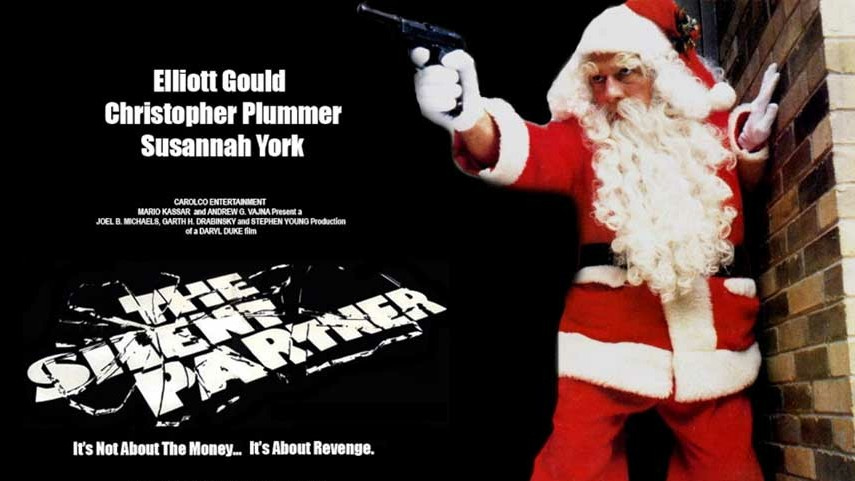

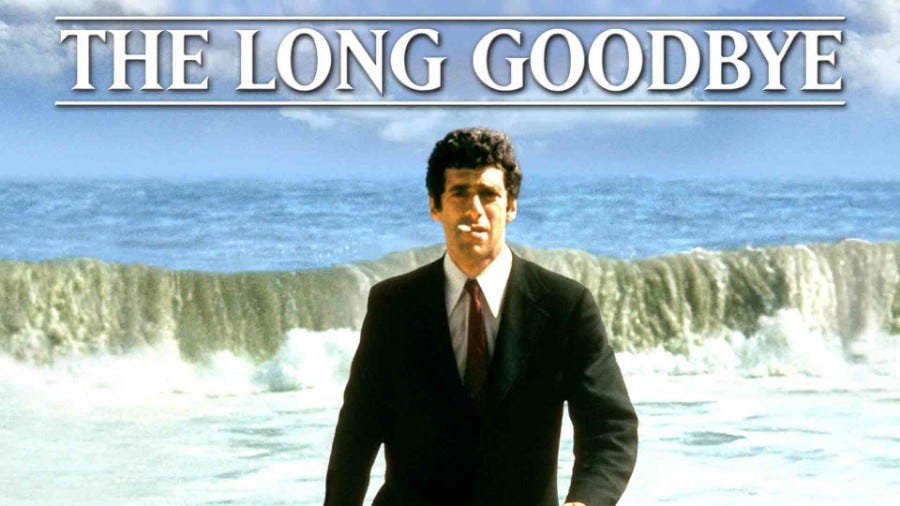

In 1973 he starred in Altman’s The Long Goodbye, where his ironic and slightly goofy mien provided the key to Altman’s sloppy deconstruction of Raymond Chandler’s 1953 exemplar of the hard-boiled detective novel, and in 1976 he teamed up with Christopher Plummer to make The Silent Partner, about a slightly goofy teller’s unwitting participation in a bank robbery.

/Amazon /Streaming /🍅75%🍿84% /Trailer /1976 /R

The Silent Partner is a taut thriller, unlike Robert Altman’s self-indulgent The Long Goodbye (see below). Directed in Canada by Daryl Duke (The Thorn Birds), The Silent Partner featured a high concept and a great supporting cast of Christopher Plummer, Susannah York, and John Candy, which fit Gould like a glove: He played a slightly nerdy bank teller, Miles Cullen, who realized before the fact that his bank would soon be robbed by his mall’s department-store Santa (a very menacing Plummer). When the time came, Miles had moved the money from his day’s transactions into an old lunch box, but reported it stolen.

The robber hears on the news the sum reported stolen, realizes that the teller must have the dufference and begins harrassing him first on the phone and then in person. Miles, for his part, is energized by the interaction in his otherwise quiet life, and enters into an audacious game of wits with the robber.

Here Gould’s persona works perfectly: his character is the kind of guy who is thrilled over the purchase of an exotic fish for his aquarium, but he’s also an accomplished gamer (which, in 1976, meant chess player) and has a few surprising tricks of his own to play on the bank robber.

Roger Ebert, in his review in the Chicago Sun-Times, awarded three-and-a-half of a possible four stars to the film, calling it “a thriller that is not only intelligently and well acted and very scary, but also has the most audaciously clockwork plot I’ve seen in a long time.” Ebert described it as “worthy of Hitchcock.”

/Amazon /Streaming /🍅95%🍿87% /Trailer /1973 /R

“You can’t go home again.” (Thomas Wolfe)

I saw The Long Goodbye at the movies in 1973, and for a Robert Altman film (he was still being lionized for 1970’s M*A*S*H), it made very little impression on me. Rewatching it recently didn’t help.

We meet private eye Philip Marlowe (Gould) in his apartment as he talks to his cat and agrees to buy some brownie mix for his neighbor while getting the cat some food. His casual air and the zeitgeist recalls the Dude in the Coen brothers’ The Big Lebowski (which was inspired by Chandler’s work), and those who remember Marlowe as played by Dick Powell in Murder, My Sweet (1944) or Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep (1946), were about to see how Robert Altman and Elliott Gould envisioned him, now in 1970’s Hollywood.

Gould as Marlowe had his unruly thatch of curly hair, mumbled to himself and others with an unending stream of unscripted wisecracks, and dressed, anachronistically for the 1970’s, in a dark suit and tie and drove a 1940’s convertible. It was as if Altman and his intended audience were sharing an unspecified joke about “straights” (in the day, it meant non-hippies). There’s some odd business where Marlow unsuccessfully tries to convince his cat that the off-brand food he bought is indeed the cat’s favorite, and Marlowe’s friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton, looking like Kato Kaelin) shows up requesting a lift—to Tijuana, after which Marlowe is picked up by a couple of detectives and brought downtown when Lennox’ wife is found dead.

Altman was famous for a chaotic directing style that featured overlapping dialog—he encouraged his actors to ad lib and today, it kind of shows. Leigh Brackett, who wrote the screenplay for Bogart’s The Big Sleep (along with William Faulkner and Jules Furthman), wrote this screenplay, too, but it’s hard to say how much of it ended up on the screen. With Henry Gibson and a scenery-chewing Sterling Hayden (who was up for pretty much anything) to help establish the film’s counter-culture bona fides, it’s a bit of a mess. Altman’s talent was for stripping the facade from filmmaking; that is, displaying everything on the screen that might better have been left on the cutting-room floor. But to what end? Best seen now as the missing link between Humphrey Bogart and Jeff Bridges’ “Dude” Lebowski.

Pete Hummers is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to earn fees by linking Amazon.com and affiliate sites. This adds nothing to Amazon's prices. This column originally appeared on The Outer Banks Voice.